(A version of this article was published in The Press newspaper, Christchurch, and on the Stuff website on 4/7/2020)

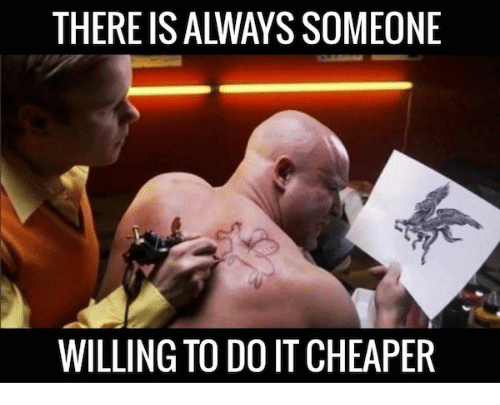

After “How much will it cost”, probably the second most common question I hear (once the shock has worn off) is; “how do I build it more cheaply?”.

There are certainly a bunch of options that can save you money, but each one has implications you will need to weigh up carefully.

Switch to less expensive claddings

Switch to cheaper glazing

Switching to a lower spec system typically means somewhat lower thermal performance and higher power bills, increased condensation etc. That said, there is a move towards the use of cheaper but high spec imported double glazing units from China which can save thousands – but rather than directly sourcing these, best to work with a reputable company who knows the manufacturer and will fit the windows themselves, and take responsibility for any problems with sizing, fabrication, NZ compliance etc. Be aware that there will usually be much longer lead times.

Spend less on fittings and fixtures

Typical issues include reduced functionality, shorter service life, difficulty finding replacement parts a few years down the track etc – which may thus cost you more in the long run. Another option is to use fewer fittings, or to wire/plumb for future fittings but defer installation where these are not critical. Cheap bathroom and kitchen joinery should be treated with caution – apart from durability issues, cheap mass home builder’s flat-pack style fittings can make a poor impression.

As with glazing, there is a growing trend towards directly sourcing cheap but good quality fittings and fixtures offshore, but much the same risks apply.

Defer some of the building work

If this is going to be required, best to plan for it up front when lodging for building consent rather than just stopping when the money runs out. Your building consent is for the work shown on the drawings and specification as submitted to council, and this is the work you must complete within the stipulated time frame (normally two years), unless you are given an extension of time, or apply for an alteration to the building consent, deleting any areas that won’t be completed (you can’t leave out anything critical).

If you have not completed the work and obtained a code compliance certificate by the time your consent expires, your work in progress may then be deemed an un-consented structure that you are not legally entitled to occupy, and that you may struggle to insure or sell in future. You will face a potentially expensive and frustrating process to try and demonstrate code compliance and have the building accepted after the fact.

Do the landscaping work yourself

Landscaping is probably one of the things most commonly left to DIY.

Unfortunately, it is also something that can strongly detract from the finished result if done by amateurs.

Most people can water a ready-lawn and plant a few shrubs, but the difference between what most people do and professionally designed and implemented landscaping is really night and day. Knowing what you like is not the same as successful design, and it could be worth considering deferring the landscaping until there are funds available to hire the pros, or at least getting good professional input early on rather than going completely down the DIY path.

Do some of the finishing work yourself

This can also seem like an attractive option for the average Kiwi DIYer – but bear in mind a professional will usually give a better result, and much more quickly. If you don’t have the skills and a lot of spare time, you may end up costing yourself as much as you save if you end up needing a professional to clean up your mistakes or you need a lot of time off work to get things done.

DIY Project Management

Handling your own project management can save you a significant amount, but be aware that this saving is achieved by eliminating the builder’s traditional margin (and thus responsibility) for managing the project properly.

By taking on the Project Manager role yourself, you take on all the responsibilities traditionally entrusted to the head contractor, without the benefit of their experience. You are now personally responsible for dealing with council, ensuring all costs are on track to meeting your budget, sourcing materials and subcontractors (knowing which are the ones to avoid!), coordinating everything and everyone so that everything needed comes together on site at exactly the right times and in exactly the right sequence, understanding in depth what each subcontractor does, and ensuring quality of work is maintained and will not adversely impact other trades, ensuring that the consented design drawings and specification are being exactly adhered to, arranging building inspector and professional (architect and engineer) visits at the appropriate times, administering all progress payments and any disputes, dealing with all of the myriad technical issues that come up, keeping good records, and all in compliance with your various subcontract agreements, council requirements, bank requirements, and the law.

If anything goes expensively wrong, blaming your contractors or suppliers or consultants will not help you if the issue arose because you, in your inexperience, made a wrong decision, or failed to anticipate something that a professional project manager would have known.

In other words, you are paying for any saving you make this way through significantly increased risk and stress.

Administering a project can also take much more time than you might expect, so you could also face a loss of earnings while the build is underway – potentially many months worth.

For many, the peace of mind that comes with handing things over to a professional who is responsible for achieving a good standard at a contractually agreed price is worth more than any potential saving.

That said, some home-owners can and do take on this DIY project manager role, often several times with successive homes – usually starting small but each time gaining confidence and taking on more and more complex projects. A helpful architect and some experienced and tolerant tradespeople you trust can make all the difference if you do decide to take this on.

Prefabrication

This is an area of growing interest to architects, and the building industry generally, and the technology is definitely advancing.

The current state of play in New Zealand is that prefabrication offers the benefits of manufacture in clean, dry factory conditions, with correspondingly increased accuracy, and reduced time required on site.

This comes at the expense of increased lead time requirements, increased upfront technical design resolution time and cost, and reduced design flexibility, particularly once the project is under way. There are also constraints on the size of elements that can be transported to site. Any wall or ceiling elements longer than a truck can carry, for example, will typically need joints designed into them, which may not be visually acceptable for many situations.

High volume but low-end housing, and repetitively designed large commercial premises and budget accommodation buildings seem to be the most amenable candidates for prefabrication, but right now you would not expect significant cost savings for a single bespoke family home.

As the technology advances and economies of scale kick in however, this is likely to change. 3D printing and other technologies will also increasingly automate and speed up the construction process, driving costs down.

Simplify the building form

Handled well, a simple building form is architecturally often better than an unnecessarily complex form anyway, for both visual and technical weatherproofing and earthquake resistance reasons. Lots of pointless junctions between roofs and corners add cost for little benefit. Handled badly or too late in the design process however, simplifying a design to cut costs risks turning an expressive and architecturally interesting building into something bland, clumsy and lifeless that will cost you much of its amenity and resale value.

Build less

Though this may not be to my own advantage as an architect, I tend to tell my clients that by far the most simple and effective way to reduce the cost of building is just to make it smaller – primarily by reducing floor area.

A well considered and more compact house can easily surpass a large poorly considered house in every meaningful way; offering better amenity, aesthetics, lifestyle quality and environmental and energy use performance – at reduced upfront and ongoing cost.

Without a level of design discipline, you can easily waste a lot of money on excessive ‘bling’, resulting in poor functionality. visually awkward layouts and cavernous seldom used spaces, and you may find yourself with a mediocre, embarrassingly oversized, tawdry and dated looking and rapidly deteriorating home for your money, that you will struggle to recoup your losses on. Focusing your money where it will do the most good is key when funds are limited, but getting the balance right is definitely an art, and far, far easier said than done if this is not your day job.

Final thoughts

Rather than crashing ahead and lining up builders and deals on appliances etc, lurching from euphoria to despair as the ‘unexpected’ costs of building (and of making wrong decisions – oblivious to the many less than obvious consequences) start to manifest, it is probably worth investing in a decent architect, and working with them from the outset to design for the maximum ‘real’ impact from your budget, as well as to keep builder costs fair and honest.

Cutting corners on design is probably one of the worst decisions anyone with a concern for costs could make.

With an architect on your team, you are far more likely to end up with an elegant home that is distinctive, practical, free from unnecessary visual clutter, that costs no more than it needs to, and that will bring you satisfaction for many years – as well as a healthy resale value!